Fallen

aviator's memory stands tall 75 years later

The Detroit News

In the woods outside a little town in Germany

stands a small memorial to an American who came to clear the sky of

Nazis.

In a handsome family plot at Elmwood Cemetery in Detroit, a copper-plated propeller

rests atop a thick patch of ivy.

The link between the two, 4,031 miles apart, is a bold young

aviator from Grosse Pointe who went off to save the world from Adolf Hitler and

died in the attempt 75 years ago.

Alfred Brush Ford lives on today in a cozy park along the

Detroit River and an enormous Hare Krishna temple in India. His name is carried

by one of the more intriguing figures in the Ford Motor Co. lineage, even if

that lineage was not his own.

On this Memorial Day, he serves as a reminder of the goodness of

people, even in the worst of times.

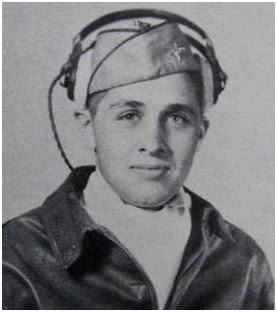

Ford was 23 years old when he lifted off for the last time in a

P-47 Thunderbolt, a single-engine fighter. The date was Feb. 22, 1945. His

group had been assigned to protect a squadron of B-26 bombers whose mission was

to sweep across the west-central part of Germany and destroy the tracks of

the Munster-Dortmund rail line.

Returning to their base, the Americans were attacked by German

ME-109s. Above Ascheberg, where a 17th-century baroque castle is now surrounded

by a golf course, Ford's P-47 took fire.

It crashed at the edge of a thicket in Davensberg, two miles

north. There, farmers found the body of a son of privilege who had come to the

Army Air Corps straight from Yale.

They buried him where he'd come to rest. The townspeople erected

a marker, a simple wooden cross with angled slats tented downward from the top

to the ends of the crosspiece. They engraved an epitaph: "Hier starbden

fliegerlodder amerik.Leutnant Alfred B. Ford."

Here died aviator American Lieutenant Alfred B. Ford. Here

stands the marker, three generations after the end of World War II and 71 years

after Ford's remains were sent back across the ocean.

At some point, the slats were covered in metal siding, and the

left side has become crimped. But the area is still tended, the inscription is

still precise and the intent is still clear.

Here stands decency.

A family of Fords

Sascha Klaverkamp is a journalist in Dortmund, the metropolis 30

miles from pastoral Davensburg.

It was Klaverkamp who wrote to The Detroit News about the cross

in the woods, "roughly one meter tall." He described the grave candle

in a metallic holder on a slab in front of it, noting that "the people

regularly place a new candle inside, and free the cross from moss or

weed."

He knew that the sun was shining on Alfred Ford’s final day, and

that eight fighter planes had battled as the bombers thundered home. He asked

the mayor of Davensberg, Bert Risthaus, why it was important to maintain the

monument, and he was reminded that wars are remembered for triumph but built of

pain and suffering.

"The cross at the crash site is a place for us to bring

that to our minds and to honor the victims of war," Risthaus said.

"And keeping the cross means keeping peace with all peoples."

From six time zones away, Klaverkamp inspired The News to find

traces of Alfred Ford in its own backyard, and to reach out to the nephew who

inherited his name.

The current Alfred Brush Ford was born five years to the day

after his uncle died. A world traveler and an influential figure in ISKCON —

better known as the Hare Krishna movement — he is waiting out the coronavirus pandemic at his home

in Gainesville, Florida.

Throughout his childhood, Ford said, his uncle was spoken of

frequently and reverently. "Apparently, he was a very good looking man.

Very well liked. It was wartime, obviously, but his death was still a

shock."

The first Alfred Ford's forebears made their fortune in banking and

railroads, not automobiles. He was the fourth child and third son of Frederick

Clifford Ford and Virginia Eloise Brush Ford, two lines replete with names on

street signs and buildings.

A 1964 Detroit Free Press article said that Virginia had been an

air warden, "and with three sons in service in World War II, she had the

eyes of a bird of prey, you may be certain."

The oldest brother, Frederick Jr., was a naval aviator. As best

Alfred Ford can recall, middle brother Walter Buhl Ford II served in the Coast

Guard.

"Everybody was stepping up back then," said Joel

Stone, senior curator of the Detroit Historical Society. "But how far did they step? I'm not

sure every wealthy family responded the way they did."

In 1943, Walter married Josephine Ford, 19-year-old granddaughter

of Henry. Now they were an auto family, and she and Walter named their fourth

child and second boy after the kid brother who didn't come home.

Alfred Brush Ford, 70, had a buoyantly misspent youth. Hare

Krishna brought him peace, and he brought Hare Krishna positive exposure, large

donations and a gift for fundraising.

He and Walter Reuther's daughter, Elizabeth Dickmeyer, bought

the Lawrence Fisher Mansion on Lenox Street in 1975 and deeded it to ISKCON for a

Detroit headquarters. Known in the order as Ambarish Das, he has since devoted

years and a reported $25 million to helping create a Taj Mahal-sized temple and

Krishna Consciousness center in Mayapur, India.

He did not feel pressure, he said, from carrying the name of a

warrior who didn't live long enough to have any frailties exposed.

"I had enough pressure from the other side of the

family," he said. "That's why I took off in the other direction."

A park bears his name

America keeps meticulous records of its grief.

Michigan, with a population of 5.3 million in 1940, sent 613,543

of its residents to the armed services. Of those, 29,321 were injured, 10,263

were killed, and one has his name on a riverfront park in Detroit.

Alfred Brush Ford Park sits at the foot of Lenox, a few blocks

south of the Fisher Mansion. It has swingsets, a playscape and two odd

relics from the Cold War: cylindrical cement radar towers for the Nike

missiles that lurked underground on Belle Isle.

On the first clear day after heavy rains, sailboats slide

quietly east and what looks like a miniature tugboat churns in the opposite

direction. Fishing lines dangle beyond railings along a sidewalk puddled by

waves.

A riverfront saloon called the Woods used to occupy part of the

property. The city acquired the land through condemnation in 1948, and it wound

up named indirectly for a 9th-century king of the Anglo-Saxons.

"My grandmother was kind of an amateur genealogist,"

the modern Alfred Ford said. "She traced the family to Alfred the Great."

A man pushing two little girls on adjoining swings said he

didn't even know the park had a name.

On a weathered wooden bench facing the river, Mark Eatmon, 61,

said the view mattered more than the sign.

He'd like to see more garbage cans there, he said. He'd like to

see a 20-yard section of collapsed sidewalk repaired, not just bordered with

orange sawhorses. The name? He just thinks of it as going to the river.

'Remember the fallen'

The name matters more in Davensberg, a few miles from Daniel

Olesch's house.

He's an amateur historian and a mechanic who lovingly restored a

leftover from the American postwar occupation, a half-ton 1942 WC-58 Dodge

radio truck. Sometimes when he’s riding his bike, he said, he'll stop to rest

next to the cross in the woods.

Only three weeks after Alfred Brush Ford died, an Allied bombing

campaign destroyed a synthetic oil plant near Dortmund and much of the city. By

April 13, Dortmund belonged to the Allies.

Thirty miles away, Olesch said, his little area had no strategic

targets. American troops didn't even stop as they barreled through.

Perhaps it's revisionist history, but he said the locals mostly

wanted the war to be over.

"It is hard to tell in retrospective, if there was a lot of

Nazi mentality in the area," he conceded in an email. "Many had lost

their sons and/or fathers during the war and knew nothing about their

whereabouts.

"So this all adds up to their true and honest willingness

to remember the fallen, no matter what side they were on."

Three German pilots were shot down in the same dogfight that

claimed Alfred Ford. One of them was a 22-year-old named Otto Balluff who'd

been rushed into the air well before he was ready to kill or be killed.

He has a monument, too — a simple sand-colored rock. Name, date

of birth, date his war came to an end.

Here a hero lies

Section K, Lot 55. Joan Capuano knows exactly where to find

Alfred Ford.

She is the executive director of the Historic Elmwood

Foundation. She leads tours of the cemetery, and she makes sure he gets

visitors.

The family patriarch, John N. Ford, died in 1881. He has a

massive gray monument in the middle of the family plot, eight feet wide at the

base and five feet tall.

The plot is surrounded by a boxwood hedge. The headstones are

all similar — thick, broad, grayish stones, with gracefully curved tops and the

letters raised instead of etched. Name, place and date of birth, place and date

of death.

The exception is the dashing young pilot.

His parents all but boasted on his metal grave marker: "1st

Lieut. U.S. Army Air Force — Fighter Pilot."

The plaque says he was killed in combat, and it says where, and

it's attached to the blade of a propeller. Not just any propeller, Capuano

said: "They found one from the same type of plane he was flying."

The pride is clear. So is the pain. "Son of Frederick

Clifford and Virginia Brush Ford," the marker read, decades before his

parents earned gravestones of their own.

The marker and the blade have turned green with age.

Beneath them lie Alfred Brush Ford, who barely aged at all, but

stood for something when he died and stands for even more now.

No comments:

Post a Comment